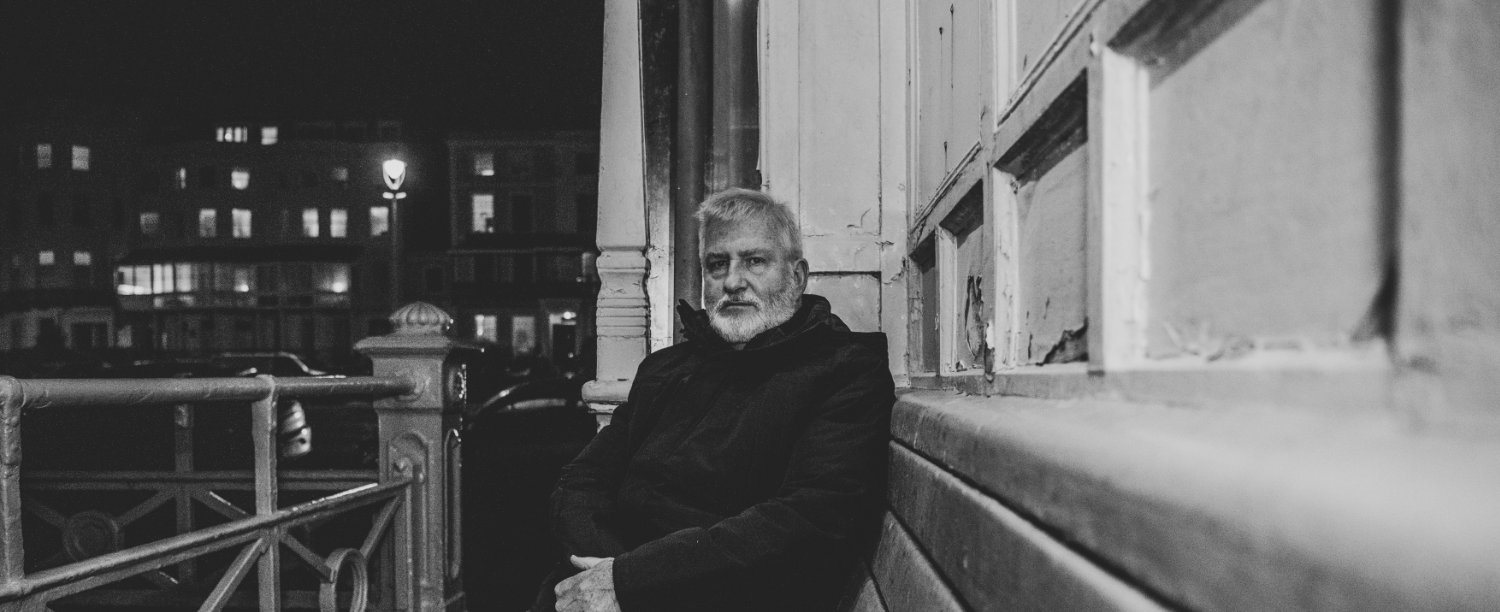

Column: Eddie Myer – Best ofs

Now it’s February, and everyone’s “Best Of 2019” lists are in, which means that culture journalists now have to cast around for some new content after an easy January. Of course this year they had to choose between a ‘Best Of 2019’ and a ‘Best Of The Decade’ – the latter now an implausible confection, because with the torrent of cultural output surging endlessly around our sensory inputs, and the political rule-book being torn up, hastily re-written then torn up again every few months, who can remember what we were listening to last year, let alone in the far-off mythical days of 2010? The decade began with the entire Bitches Brew tapes being released, against their creator’s intention and to no-one’s particular edification, and finished with a previously-unreleased Coltrane album in the UK charts, closely followed by yet another ‘lost’ recording, Blue World. Meanwhile, Kind Of Blue remains a fixture on the bestseller lists. 2019 was the year in which physical sales passed a tipping point, accounting for less than half of UK recorded music revenues, and as we’ve remarked before in this column, streaming is still not a format that’s very favourable for monetising jazz. With those kind of odds against you, who would chance their arm or risk their shirt on releasing a jazz album?

Yet release they do. 2019 presented jazz lovers with an embarrassment of riches: releases that were either superbly conceived and executed in the tradition, upholding its finest values, or else that took a risk, and impressed with their sincerity and integrity. As examples of the former, we can at least mention outstanding releases from Quentin Collins, Nigel Price, John Turville, Rob Luft and Dave O’Higgins, Paul Booth, Jean Toussaint and newcomers Gabriel Latchin and Mark Kavuma: for examples of the latter, an embarrassment of riches: who could choose between Neríja, Seed Ensemble, Sarah Tandy, Binker Golding, Theon Cross, Duncan Eagles, Preston Glasgow Lowe, Alex Hitchcock, Miguel Gorodi, Andrew McCormack, and Brighton’s own Anöna Trio, to name only a few? Let’s be thankful for the labels such as Ubuntu, Whirlwind, Fresh Sound New Talent, Jazz Re:Freshed, Gearbox and Ropeadope that are prepared to risk their time and money to bring us these treasures.

We’re doubly fortunate in that all the above artists have performed in Brighton to support their releases, many of them at our own Verdict club. Without needlessly denigrating the genius of its composers and arrangers, jazz is a spontaneously generated artform, and it’s an often repeated cliche that a recording can be seen as a snapshot of the music as it was on that particular day, one of an evolving series of performances, rather than a definitive statement: seeing the band live enriches the experience of listening to the record. Jazz lives as a live artform, but if funding a jazz record is a risky investment, the life of a touring jazz musician is hardly a pathway to riches either. This column has already dwelt at some length on the financial realities of the jazz musician’s life. Of course, individual incomes are a closely guarded secret, known only to the musicians themselves, their dependents, and those kind folk at HMRC: full disclosure is rare, and a fully researched investigation, while fascinating, would require a great deal of time, trust and goodwill. However, as a pointer, the Musicians’ Union advises that a musician giving a single performance (max 3 hours) plus rehearsal on same day (max 3 hours) in a venue with a capacity of less than 200 (which amply covers the majority of jazz gigs) should receive a remuneration of £146.00. Recently released analysis by the Office Of National Statistics put the UK’s average full-time salary for 2019 at £36,611, so in order to achieve this average, our fictional jazzer would have to play 250 gigs at the full MU rate every year. We will be giving away no secrets if we acknowledge that many jazz musicians will not achieve either the quantity of gigs nor the quality of fees necessary to hit this average. Wages nationally are, in real terms, still worth less than they were ten years ago: wages for casual pub sessions in Brighton (and nationally) are still the same as they were twenty years ago, whereas the cost of goods and services as calculated by the Bank Of England have risen by nearly 75% and you’d need nearly £70 to buy what you could have bought for £40 in the far-off days of 1998 – and let’s not even mention the rental situation.

Of course, many jazz musicians exist on a portfolio career balanced between echt jazz performances, more mundane fare such as cruises and pantos, teaching, and other diverse activities. And, fortunately, we still have the Arts Council and its stash of Lottery funding to disburse. The artist’s path has never been an easy one, and no-one owes them a living: let us admit that even in the Golden Age of jazz, an unswerving devotion to playing bebop led many artists, whose deathless musical talents unfortunately far outshone their fiscal abilities, to lead lives of chronic financial insecurity. So the choice is ours to make. None of this wonderful music would be able to thrive were the talent that creates it not underpinned by the support of you, the listener. So whenever you can, go to the gig, and, if you can stretch to it, buy the CD or the vinyl as well. You’ll be enriching not only the musician and their backers, but yourself, and ultimately all of us as well.

Eddie Myer