Improv Column: Out Playing by Wayne McConnell

Out playing is all about playing against the harmony. Its playing the 'wrong' notes at the right time. Out playing isn't just random, it still must have all of the melodic content of inside playing such as development of ideas, rhythmic interest, space etc. It must say something. So if out playing is not random notes and it's not playing the original harmony of the tune, what the heck is it and how do I practice it? The short answer is, listen to the players that you love that you feel play out. Since there are no ‘rules' as such, you have to find out what outside playing means to you. You also have to find out what is acceptable to you musically. It is also worth saying that if you play outside without much 'inside' knowledge your playing might not be as effective and you might not reach your audience as much. Out playing must make musical sense, it must somehow be connected to the song or how you feel about the song.

So if playing out means playing the notes that technically don't belong to the harmony, how do you go about trying it? I think it is about unlocking the sounds in your head first. It is very hard to hear the 'wrong notes' while the normal harmony is going by. Give it a try yourself, play a chord, let's say a Dm7 and try and sing a note that doesn't belong to the chord. Don't just sing out of tune or sing badly, but really try and hear a note that doesn't fit. It is important to try it with your voice first because it would be easy to do this on our instruments by playing a note a semitone above or below any chord or scale tones. If you found that easy then well done, most people cannot do it or find it very difficult.

So what we must do is to unlock these unfamiliar sounds by making up some exercises. Alongside this, you must be listening to musicians who play in an outside way. This will help to unlock the sounds. For me, I prefer musicians who have a good balance of inside vs outside playing: Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Woody Shaw, Dave Liebman, John Coltrane, Brad Mehldau, Mulgrew Miller and Geoffrey Keezer to name a few. In fact, have a listen to pianist Geoffrey Keezer on some of Ray Brown's final recordings. Keezer keeps Ray happy by playing swinging, bluesy, tradition stuff then for a couple of choruses, he'll go into outer space. His outside playing is so much more effective as a result. Every musician who can play outside effectively knows when to resolve lines and when to leave them open. It should be the perfect balance between surprise and the familiar.

Logic is Everything

Since the notes in outside playing do not correlate to the harmony, we must find structure elsewhere for the listeners to accept it as valid music rather than jumbled noise. One way of doing this is to play outside for a small amount of time only to resolve inside the chords. You can practice this on one chord by firstly playing inside the chord then moving out a semitone above or below for a few bars then moving back. You can heighten the sense of logic by playing a sequence in an arc shape. The sequence would start inside, keep ascending or descending, move outside and then back inside again. It's not easy to make it sound and intended straight away. It takes a lot of listening and practicing.

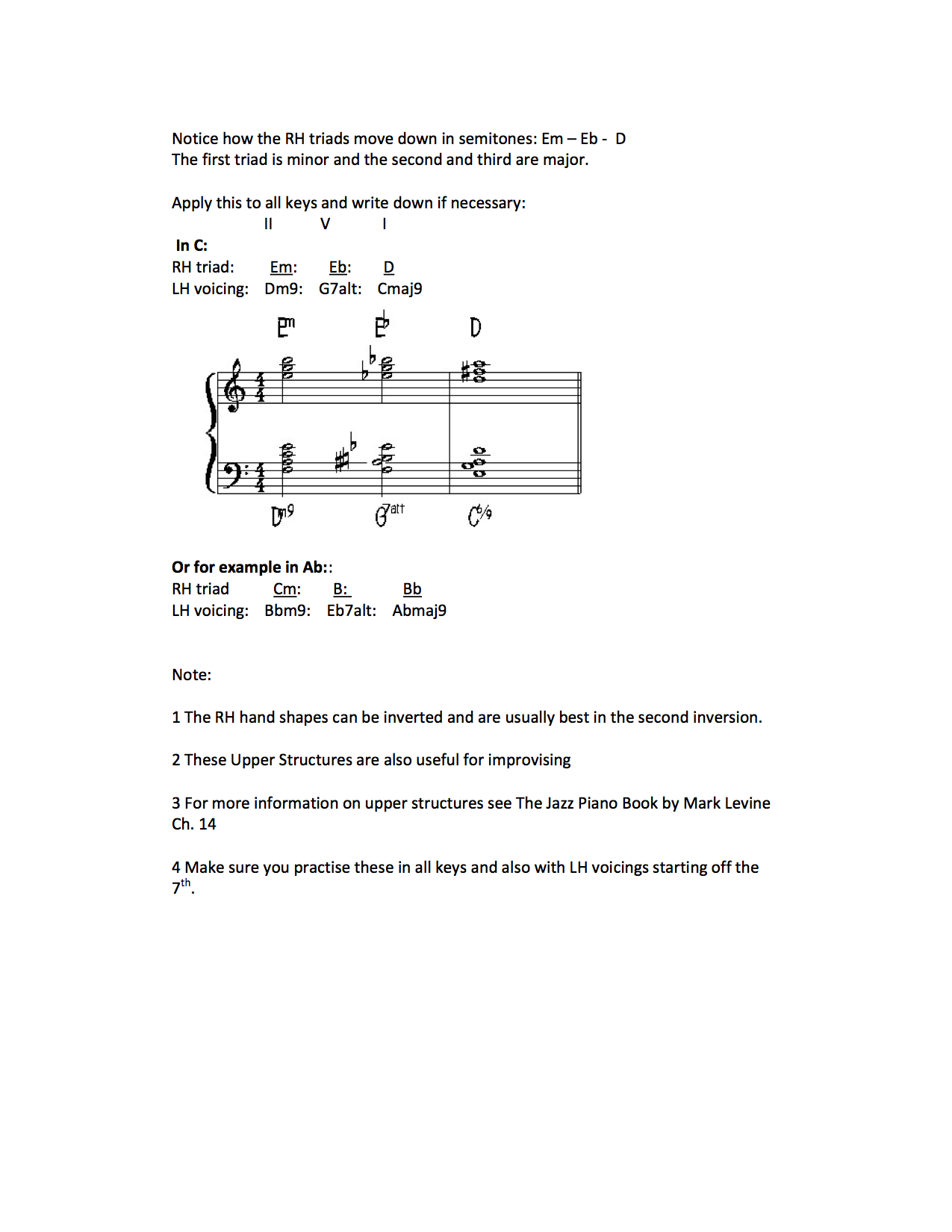

Sticking with the theory of being logical, our brains like patterns and familiar structures. Because of this, we can use structures that we are already familiar with to inject a bit of 'outside hippness'. We can use triads, seventh chords and perfect fourth shapes to play outside.

Triads:

Triads offer a great way to create a layer of familiar structure. Everybody, musician or not can recognise the sound of a triad. We hear it everyday. We can use that fact to convince the listener that what they are hearing is structured and logical. In fact, triads are used in inside playing in the form of upper structures. An upper structure is simply the upper extensions of the chord. For example, if you play an Ab triad over a C7 you get C7b13b9 or C7alt. What I'm talking about though is simply harnessing the sound of the triad. Try playing major triads build from each note in the C major scale. You can of course try this on minor and dominant chords too.

Chord Structures:

Let's take a C major 7th chord. C E G B. If we were to extend this chord we could add another 7th chord on top D F# A C#. Play these two chords together on the piano in the middle register. Beautiful right? I think so. This 'polychord' gives us a 'Lydian' sound with that C# (arguably a very dissonant note against a C major). The C# doesn't really function as a b9 sound so I guess it would be better to call it the #15. Let's take the major 7th chord structure and build a major seventh from each note in the C major scale. So: Cmajor, Dmajor, Emajor, Fmajor, G Major, A Major, Bmajor. Play around with these shapes with a play-a-long just playing Cmajor 7. The effect is definitely outside but the logic and structure of the major sevenths somehow allows us to accept the sounds. Don't worry if they sound very dissonant to start with, it's about unlocking the sounds and finding what is acceptable to you. If you find Bmajor too much, fine, don't use it until/if you feel ready for it. As this is more of an exercise, start by playing inside then go into using the 7th chords and then back to inside playing. Listening to the experts and experimenting is everything.

Fourths:

Fourths work in the same way, they create structure. Mark Levine in his book 'The Jazz Theory Book' describes this as being 'in the key of fourths'. What he means is that once your ear hears fourths or triads or 7th chords, the ear wants to hear more fourths. This allows us to take liberties with the harmony to extend the melodic pallet beyond what the underlying chords say. For example over a tune like So What when you have long stretches of one chord, try playing a pattern of fourth shapes initially diatonically in the key and adding in the odd one a semitone above or below. Dm7 – DGC, EAD, FBE, GCF, AbDbGb, ADG, BEG, CFB. When you play them within in key, it produces some chords that aren't strictly perfect 4ths but tritones instead. The sound of the tritone adds 'bite' to some of the chords/shapes.

Join me in a couple of months for part 2. Happy practicing!