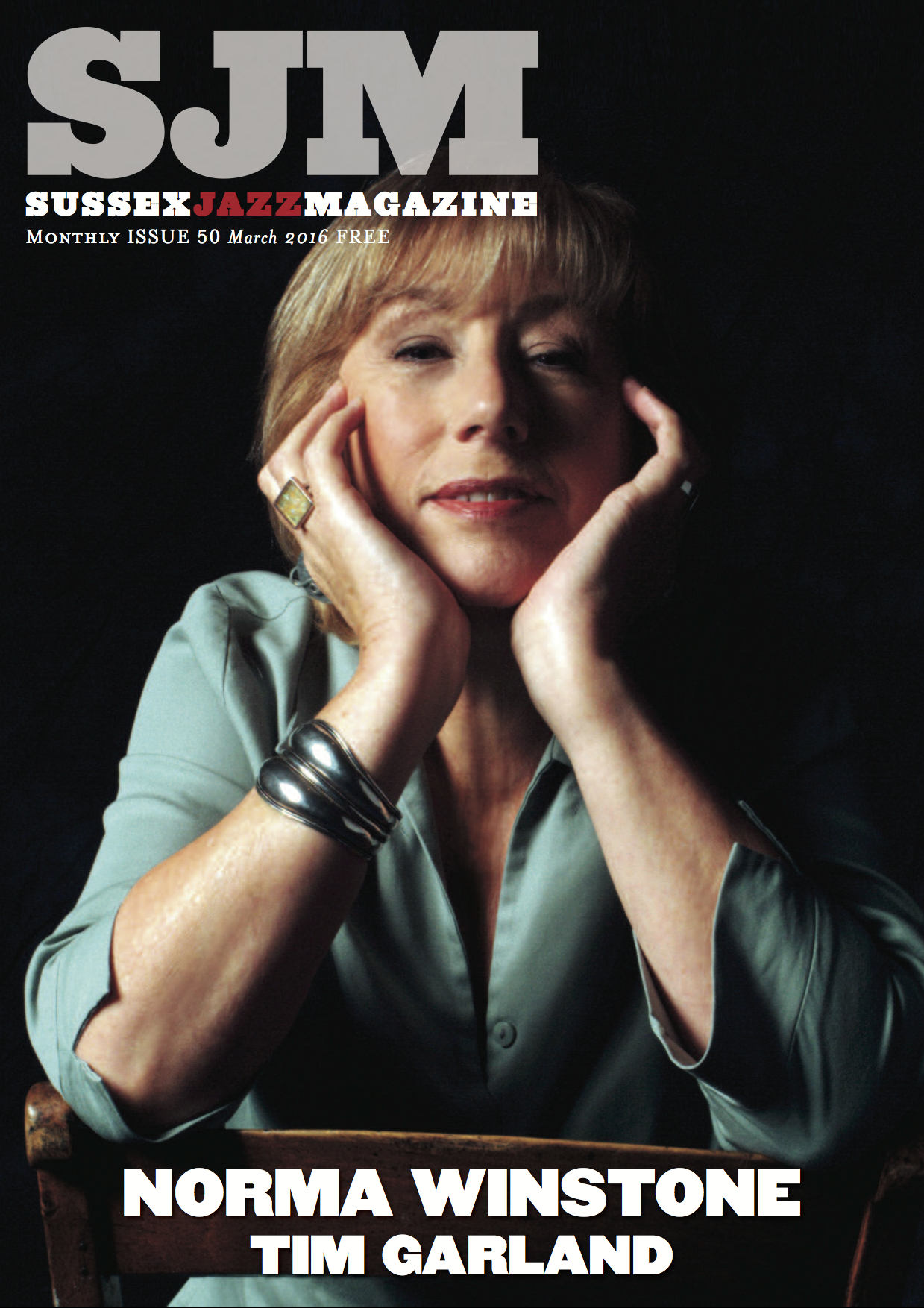

Norma Winstone Interview

Lou Beckerman discusses with the highly respected British vocalist and lyricist, Norma Winstone MBE, a flourishing life in jazz spanning over five decades.

Most of us can't remember a time when Norma Winstone wasn't a prominent figure on the British jazz scene. I first met her three years ago when I was a student on a jazz course and Norma was teaching some complex vocal harmonies. It was a delight to link-up with her again at this year’s South Coast Jazz Festival where she was due to perform that evening in a sell-out gig with Nikki Iles’ Printmakers.

Norma, ‘grande dame’ of jazz, has been awarded a formidable array of honours over the years: top singer in the 1971 Melody Maker Jazz Poll, MBE for services to music in the 2007 Queen's Birthday Honours and the Skoda Jazz Ahead Award in 2009 for her contribution to European Jazz. In 2010 she was recognised in the London Awards for Art and Performance, received a Lifetime Achievement Jazz Medal from the Worshipful Company of Musicians and became an Honorary Fellow at Trinity Laban Conservatoire – incidentally the first Jazz Fellow. More recently in 2013 she became an Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music. She was the 2015 Parliamentary Jazz Awards Jazz Vocalist of the Year and, in the same year, was also presented with a Gold Badge of Merit from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.

Lou Beckerman: “Norma you’ve been described as a singer, lyricist, improviser and educator. I’m assuming that each of these informs the other but is there one of these that you feel comes the most naturally to you?”

Norma Winstone: “I think singer is obviously the first one. The lyric-writing came when I was wanting to expand my repertoire to embrace the lovely music I'd heard but that didn't have any words. I'd done wordless singing and improvising, but some pieces feel as though they can incorporate lyrics though others, to me, feel complete without them. I'm into the idea of the voice as a sound as much as anything.” “As an instrument?” “Yes – but 'voice as instrument' doesn’t mean trying to be a saxophone or a trumpet. I think of the voice as a sound and, as a singer, we've also got the added option to use words whereas instruments don’t. I didn’t know any lyricists and didn't even really know that I could do it until I started trying. Kenny Wheeler was the first one to ask me to write words (for an incredibly difficult piece). But I also remember writing lyrics to Egberto Gismonti's Café (which I fell in love with when I heard him playing it with Jan Garbarek) and thought they seemed to work. So I just went on and did more… and more. So I suppose the singing informed the lyric-writing and now the lyric-writing informs the singing.” “So they all dovetail…” “Absolutely.”

“Historically, vocalists have often had a reputation of being ‘singers’ – not necessarily ‘musicians’… I believe you learned to play the piano and to read music as a child. Do you think without this background you would have been able to be so exploratory or, indeed, to collaborate as you do, as there weren’t at that time the opportunities for jazz education that currently exist?”

“No – definitely not. You couldn't learn about jazz…there were no schools. Now there are academies and it's an accepted art-form worth pursuing as a career. But at that time there wasn't anywhere you could even learn about singing apart from classical singing or musical theatre where they'd teach There's No Business Like Show Business and I didn't want to do that. So I just learned everything by listening. When I was about seven I had eighteen months of piano lessons. These stopped when my teacher, who used to come to the house in Bow (where I was born), became pregnant and ceased teaching unless I could go to her home. There was no way I could get there. We didn't have a car. Then we moved and I couldn't find anybody I liked for piano lessons.”

“I never got to a very high standard although I did get a ‘junior exhibition’ – as it was then called – to Trinity College. My class teacher in the new junior school played the piano and recognised that I was musical. Application forms for a junior exhibition came round. I didn't take one – didn’t think I’d be eligible – but my teacher thought I should. So she offered to coach me after school and I took the first exam – getting through, much to my surprise, as I didn't know much apart from the key signatures; could read the notes and play different things with left hand and right hand.”

“Anyway I was then sent to Trinity College for the next entry phase and I had to be able to sing to get in. But it didn't occur to me to do singing as a study. I loved classical music and operatic arias but I never envisaged myself singing them. I didn't want to sing like that. Anyway they weren't accessible but songs were. I wanted to sing like Frank Sinatra who I was brought up with and who I adored – and still do.”

“So I went up to Trinity on Saturday mornings for three years. I took organ as a second study but was rather put off in the winter when I had to go to the church to practise. I'd run in there, switch on all the lights and the organ which would produce eerie sounds. It was frightening for me aged only thirteen or fourteen. Then it came to doing GCEs and I thought ‘I can't do this’. They made us play in a concert before an audience at the end of every term and I was terrified of playing the piano in front of people. So I left.” “And they didn't help you with that?…Didn't teach you any techniques?” “Well no – you just had to do it. Just as you didn't get counselling for all sorts of things; you just had to get on with it – or you were obviously not meant to do it! Which I don't think I was! However I did reach a certain level on the piano.”

“Were your family encouraging?”

“Yes. My mum and dad loved classical music and jazz. Dad adored Oscar Peterson and Fats Waller. I was brought up listening to that music. But we had no record-playing equipment so we listened to things on the radio. Radio was everything. This helped me to be quick at learning… There was no way I could record anything so if I heard a song that I liked I had to really focus on it and think ‘I'll learn the next bit the next time I hear it’! And of course the kind of music we're talking about featured Sinatra on the radio. My mum knew loads of standards and I'd ask her, 'How does this one go?…What are the words to that…?’ and she'd tell me. They weren't musicians as such but my dad could knock out a tune on the piano by ear and mum had a really nice voice and a very good ear. Later, when we were living in Dagenham, if you played anything in our tiny house everybody heard it. By then – in my teens – I’d got a Dancette record player which would play one seventy-eight. I bought Frank Sinatra and we'd all stand there and listen then turn it over and play the other side. Then I got something I could play LPs on. I think Ella and Louis was my first ever LP that I saved up for, and then Oscar Peterson. His playing was so fantastic – very held back and absolutely beautiful. I‘d heard a swing record on Radio Luxembourg. Somebody recommended Miles Davis. I got Kind of Blue and that was it – I never looked back. I used to hear my mum whistling Miles Davis solos while she was washing up!” “So you would have imbibed all of that…” “Yes, music was always a focus in the family and we'd always talk about things we’d heard. In those days we had a piano which had belonged to my grandmother. She gave it to me when we moved so I'd have something to practise on.”

“So you left school having decided to be a singer?”

“Yes but I had no idea how to start! I heard of a singing teacher – Al Dukardo (I think ‘Duke’ was his real name). I don't know whether he was a singer – he played the piano and I think saxophone – but I never heard him sing. The first thing he said was to take a deep breath and so I breathed into my chest and shoulders and he said ‘No, no, no! I'll teach you how you are supposed to breathe for singing and playing instruments. If you sing like that no-one's going to hear you anyway!’ So he taught me about the diaphragm and gave me all these exercises on long notes which I’d also hear being practised on instruments.”

“I had a little voice (I don't have a big voice anyway) but these exercises were all I knew so I practised. It took years really for me to gradually get anything like a sound that I could bear to listen to. I hated my voice but some people seemed to like it and this was what I wanted to do. I thought as I didn’t have to actually listen to it I’d do it – I'd sing! It wasn't until I was recorded by ECM – the first Azimuth album that I heard my voice and thought 'Is that me?' I'd never sounded like that (though probably that I'd never really been recorded that well before).”

“Having had these lessons with Al Dukardo he said he could get me some jobs with friends who had bands and I started to work with them doing function gigs. But it wasn’t really what I wanted to do so I stopped singing for a while. I didn't give up the idea of singing I just realised I hadn’t found the right kind. I kept collecting songs that I would sing if I did ever meet the right people. I had a job in an office and was wondering if I could perhaps go to other jazz venues and see if I could sing in those. Finally somebody where I worked noticed me answering an advert in the Melody Maker for a jazz vocalist and said I should go with her to a pub in East Ham: The Black Lion. There was a trio playing there so I went along and asked if I could sit in. They had a singer but said he was leaving in a week or so and would I like the gig? I suddenly had two nights a week singing in the pub and I met all sorts of people through this. And of course I met John around this time.” [Norma’s former husband, pianist John Taylor.]

“I remember once – Ronnie Scott and Tubby Hayes were playing in a place. I screwed up my courage and went and asked Ronnie if I could sit in and he said 'No!'” [Much laughter here!] “And I don't blame him either!”

“I remember my mother somehow getting her hands on some bits of music and giving them to me. They must have been copies from old Real Books. They had lists of songs and chord sequences and I remember I had this job in Germany, which was pretty awful, with a group playing American bases and for something to do I thought I'd find out which key I did these songs in and so I started transposing. Well it's a mechanical, mathematical thing going down a major third or whatever it is. And of course it helped that I had learned piano.”

“At one time I was co-hosting a club in Hackney called The Regency Club (which was actually owned by the Kray twins! I had no idea then who they were or that it was owned by them – I only found out afterwards!). Anyway it was just an opportunity for me to sing. We had a trio and we used to invite guests – though I’m not sure how we found them. One was Ian Carr [trumpet/ flugelhorn]. One night Ian suggested I should sing with a new jazz orchestra and he introduced me to Neil Ardley. I suddenly found myself singing with this big band which was fantastic. Michael Garrick was on piano. He gave me some songs he’d written and I learned them. He asked me to sit in on a gig and to sing one of these songs. Then I was invited to stay and join in on the next piece which had no words and I didn't know it. He said ‘take a solo’, so I did – without words. One of the saxophonists was leaving and I was asked if I wanted to join the band and sing the saxophone lines. It was fairly unusual in those days for singers to have any idea of reading and, of course, I couldn't have done that if I had not learned. I've never considered myself a really good musician though I've got a good ear and I can read and figure things out and hear chord sequences.”

“I believe you began your career singing standards though I don’t think you sing many standards – if any – anymore? (Although your own ‘Ladies in Mercedes’ has become a classic in its own right!)…”

“I do sometimes sing standards. Even with ECM Records I've recorded standards. With my current trio we did Every Time We Say Goodbye – a very unusual version but it was all there – the melody and the words. I do like standards but I found the problem was that I didn't really think I had anything to add – as far as a voice was concerned – if you've already got someone like Sarah Vaughan (what a voice!) and Ella and Carmen McRae whose voices had a terrific character. I felt that mine didn't really and I didn't know what I could bring to those pieces. But I do love the standards and love singing them. We sometimes play them in tonight's group [Nikki Iles’ Printmakers]. The thing is I started singing standards because I was influenced by the people who sang them. That was the music.”

“How did you first become involved in what’s described as the ‘avant garde’ movement of the 60s and early 70s, and begin to find your own voice – in the broadest sense? How did you first formulate the idea of using your voice as an instrument – taking your music and distinctive sound to another level?

“I realise now that when I heard Kind of Blue in the late Fifties / early Sixties, I felt there was something in this music. I thought a voice could be in it in a satisfying way though I didn't know how. I didn't want to come along, sing a melody and then everybody improvise and I would sing the melody again. (Actually I'm quite happy to do that now but at the time I thought I've got to do something else.) I supposed if I could get words to things like So What or Freddie Freeloader then there'd be a way of including the voice. But I didn't really know then what the voice would do.” “Did the improvisation come easily to you?” “I used to improvise by keeping the words and improvising a different tune with them. I didn't sing wordlessly but it was kind of unusual, different and was a step in the direction though I didn't know where it was going…”

“And you first attracted attention when you sang at Ronnie Scott’s…”

“A friend of mine who was playing at the Charlie Chester Club invited me to come along and sit in. John Stevens, who became the leader of Spontaneous Music Ensemble, was on drums. At that time none of us knew about free jazz or anything experimental, but he liked my singing and told Ronnie Scott, recommending that he should give me an audition. It took about eight months, with me in the end having to get Ronnie to hold to his promise – which he finally did. By that time I'd already rehearsed with Gordon Beck [piano] and Jeff Clyne [bass]. John Stevens knew them and set up a rehearsal for me. I mean Gordon and Jeff were stars. I was terrified.”

“By the time the audition for Ronnie Scott's came through John Stevens had discovered free music – wasn't playing time any more. Funny thing was that Gordon Beck told me this but said not to worry as he had a drummer who had just come down from the north. It was Tony Oxley. That was my audition trio: Gordon Beck, Jeff Clyne and Tony Oxley! Anyway Ronnie gave me four weeks at the club, which is what they used to do then. But John Stevens was about doing his free stuff and there were a lot of things going on. He was setting up things on a Saturday morning and said to come along to one of them and just join in. Kenny Wheeler was there on one and Dave Holland before he went to join Miles Davis.”

“And in the meantime I was with Kenny Wheeler doing free music. He had his big band and used to do broadcasts once or twice a year. He invited me to sing with the band. He did an arrangement of a standard for me which we played and for the next broadcast he'd automatically written me in as a voice in the band. So in the end I was doing this thing where I'd imagined a voice could be in the music when I'd heard Kind of Blue. That's probably what I was envisaging though I didn't know I was thinking it at the time. It was an unknown thing – an aim that I had.” “When nobody else was really doing it?” “I didn't hear anybody doing it. I think there were people like Jay Clayton in the States. She was doing more experimental things like that. Actually for a while people didn't seem to be interested in standards. Mike Westbrook came along and asked if I'd join his band. He'd written a piece called Earth Rise which was obviously for the moon-landing and I joined in on that. Some of those pieces had words and some didn't.”

[Azimuth, the jazz trio, was active from 1977 to 2000. The ensemble was composed of trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, Norma on vocals and pianist John Taylor. The trio was described by Richard Williams in The Times as ‘one of the most imaginatively conceived and delicately balanced of all contemporary chamber jazz groups.’]

“You have been, and still are, a torch bearer – an inspiration in the forefront of British jazz …Was there a major influence along your own path… and would you say you’d learned primarily from vocalists or from instrumentalists?”

“I learned about singing a song from Frank Sinatra and I learned a little bit about singing without words from Ella when I heard her scat singing. I just learned it as I had when I listened to Miles and also when I listened to Paul Desmond. I didn't know he was improvising because it sounded written. I was obsessed with the music so I would play these records over and over again and in the end I learned the solos without trying too hard. I realise now that I'd found out about improvising but I didn't really know what I was doing – and I still don't know what I'm doing!”

“Your lyrics are very skilful – they could almost read as poetry. Have you ever written poetry?”

“Only at school – not since. Sometimes I will just jot down something if an idea – a phrase – comes to me. But I love poetry. Often if I have a project to do I'll sit and read poems to be inspired. And sometimes I’ll just get one word which I could perhaps use. Or if it's something I've dreamed – I'll just write it down so I don't forget it. I don't necessarily do anything with it; it’s just there.”

“And would you say your lyric-writing is emotionally or musically driven?”

“Well it's driven by the music but I can't seem to write to something if I don't have an emotional reaction to it. I can't do it just as a job. I think the best lyrics come from an immediate emotional reaction to a piece.” “And which comes first – the melody or lyric?…” “The music for me always comes first. I don't think I've ever written words without having a melody to work to.”

“You’ve sung and collaborated with so many different band formats and currently you seem to have a very natural home in a trio setting with German reedsman Klaus Geing and Italian pianist Glauco Venier. I personally love the utter spaciousness of this work (Stories Yet to Tell, 2009)… Can you tell us a little about this collaboration?”

“Glauco and Klaus asked me to join them for a concert. They were playing as a duo and they'd got some funding from somewhere to have a guest for a couple of concerts. The agent asked me if I would sing. But for a long time I'd been doing things that people asked me to do and it was their music and I would sometimes come away feeling that I hadn't done myself justice and so I was tired of it. I really wasn't keen but he reminded me that I had worked on a recording session with one of them – a session for an Italian drummer – one of those things that I'd said I wouldn't do again. But I remembered Glauco. He would often play in-between the pieces we had to record (some rather strange pieces!). I liked what he was playing – sometimes a standard. Sometimes we’d both have the earphones on and I’d start singing so we’d connect in that. So I agreed to do it but on the condition that I would send the music on ahead and they’d play what I wanted to sing. They were happy to do this as they knew Azimuth and Somewhere Called Home. We played mostly that kind of material and I brought some Fred Hersch pieces. As soon as we played I just knew I could work with these two. I loved Klaus’s beautiful and incredible sound on soprano and bass clarinet (although he’s really got more into bass clarinet since then). The agent suggested we record our own material so that it wouldn’t be confused with Azimuth or Somewhere Called Home. So they brought some pieces and I wrote words to them. I realised that they were both very open. Glauco doesn’t mind if he doesn’t solo – he just wants to make the music. They play for the music and I love that.”

“You’ve obviously worked very hard. Were you extremely disciplined in your practise habits? Can you share suggestions regarding practice time?”

“No!” [Candidly and to laughter!] “I was just thinking today that I hope my voice is there as it hasn’t been working much lately so it’s a bit foggy.” [Clears her throat but admits that singers are not supposed to do that…] “I don’t know if coughing is any better and I’ve been doing that a lot! But no, I’m not disciplined really. I can work very hard, especially if I’ve something to learn and I love doing that. Otherwise what I normally do if I want to do a vocal workout is find something that’s really hard to sing like a Kenny Wheeler big band piece and sing that. But I don’t really have a schedule.”

“You’ve had, and continue to have, a prolific recording career… can you talk a little about this? Do you have particular producers you like to work with and who produce a particular sound you have in mind?”

“There’s only one producer that I know – Manfred Eicher” [German record producer and founder of ECM Records]. “He’s incredible. I think with Manfred it’s that he had a vision of a sound that he wanted for that record label and it worked. And it’s still working. His work has a direction and the label has influenced so many people. I’ve never really been produced by anybody else. It’s hard for musicians to produce themselves even though we try. We think we know but I like to have an outside ear.”

“If I were to recommend an album which might typify Norma Winstone is there one that you feel defines you as an artist? Or, if not, one you are particularly proud of?”

“That’s a difficult one. I don’t really know of anything that defines me. I suppose Somewhere Called Home (1986) is the one that everybody says is the definitive one as Tony Coe’s clarinet playing is incredible and John [Taylor] is incredible. And I just love the pieces on it. And then some of the Azimuth recordings such as Azimuth 85. I would say these two, although between them the Azimuth recordings with wordless pieces might define me more whereas Somewhere called Home has many lyrics. But I’ve forgotten a lot of recordings and when people mention Labyrinth [the 1973 jazz-rock concept album with Ian Carr's band Nucleus.] I recall recording them but don’t really remember what the content was. There was Symphony of Amaranths, the Neil Ardley poem settings with orchestra. Then my first album Edge of Time which I was never very sure about. I was sure at the time that this was what I wanted to do but I didn’t like the sound of the voice on it. And then there were all the things I did with Kenny [Wheeler] like music for large and small ensembles.”

“I very much use words with the current trio, but I don’t feel hemmed in; I don’t feel I’ve got to sing words. Of course we use more improvisation playing live than we do on recordings.”

“How did you feel when your 1972 notable album Edge of Time was re-issued forty-two years later in 2014?” [One reviewer, rather fondly I thought, spoke of how Norma’s vocals in this album ‘mutate from cut-glass articulation of her own lyrics, to slightly bonkers ululations that soar high above the ensemble freak-outs’.]

“When I was asked I said ‘no’ to begin with. I didn’t want to go back. Then I thought about it and I realised it was a little piece of history” “Those moments in time that make up history…” “Yes – so I agreed.”

“You are obviously a great innovator and have played a prominent role in shaping a particular genre of vocal jazz but how do you keep your music fresh and continue to push the boundaries?”

“I think I’ve pushed any boundaries I was going to push! It seems to be enough for me. But within those already established boundaries I suppose I could do an album with just voice overdubs but I like working with people. And I like harmony. And I like time. I do also like freedom. I mostly find the people that I like are doing free music – like Kenny Wheeler – well-rooted in harmony. I do also like Evan Parker on saxophone who completely does his own thing. He’s been on his own path for all these years.”

“How would you describe your music?”

“I wouldn’t know how to! Except that it’s a result of having loved good singers of standards, jazz musicians, improvisers and classical music. I think all this came very much together with Azimuth. There were times which were very Debussy-ish or even Bartok. John loved Bartok. It just seems to be a combination of all the music I’ve ever liked.”

“How important is it for you to be an educator – to pass on what you know from your experience and knowledge…”

“Well I’m happy to pass on anything IF I can do it in an enjoyable way. If there is somebody who knows what they want from me then I’m happy to give it. But I’m not that keen on trying to spark somebody’s enthusiasm – I wouldn’t want to do that.”

“One of my own passions in teaching is to empower people to move beyond their magic-stifling performance anxiety. Have you, like so many, ever suffered from ‘stage fright’ and do you have any of your own strategies to share?”

“Well yes. When I started I was so nervous. I was so scared of singing I came up in rashes. But I just kept at it as that was what I wanted to do. And it’s like a baptism of fire. Good breathing – diaphragm breathing – always helps. But I don’t really have a strategy. One thing I do remember Jay Clayton saying – and I think it’s very apt – to just think about the music, not yourself. Most of the time when we’re stressed it’s because we’re thinking what people are going to think of us (including how we look and we can’t really get away from that!). If you think about the music and communicating it then you’ve really got a chance.”

“For all of us our voices change with the passage of time. Do you embrace these changes as something positive? And is there anything you do to in particular to take care of your voice?”

“Well I’ve dropped a few notes from the higher range but then I’ve gained a few lower ones which is quite nice! I had those high notes when I needed them for Azimuth and Kenny’s stuff but I don’t know that I do need them anymore – I don’t really do so much of that. So it’s mellowing a bit now.”

“Is there published sheet music of your work (or transcriptions)?”

“There isn’t as yet. We keep talking about this – Nikki [Iles] is often saying we should publish a book of songs which I’ve written lyrics for. So that might happen…”

“What do you feel when other people sing your compositions? For example I know A Timeless Place has been recorded by a number of artists – the late Mark Murphy amongst many others.”

“Yes – it’s fine. Often they’ll take the words from a recording and if they get in touch with me I have normally sent them a copy.”

“Many female jazz vocalists have enjoyed very successful careers, giving the impression that gender posed no obstacles. You’ve had enormous courage in advancing musical frontiers… Have you also needed courage as a woman in jazz? I am curious whether you, as a female improviser and innovator ever experienced any hint of gender discrimination in your earlier days.”

“No. I know I’m unusual but if you talk to Nikki she never has either. I’d try to ignore it if it happened!”

“Can you tell us a bit about your work with Nikki Iles’ Printmakers who you are performing with at South Coast Jazz Festival this evening? How the band formed?… [Nikki Iles: piano; Norma Winstone: vocals; Mark Lockheart: guitar; Steve Watts: bass; James Maddren; drums.]

“As a singer in the band there will always be people who think it’s your group so it’s advertised as her and my group but it’s really Nikki’s band. She had the idea to get all the people together that she really liked and who she thought could impart their special imprint.”

“I was wondering about narrative in a piece. For instance the conceiving and crafting of the track O in your recent Printmakers album Westerly. I think of it as an evocative sound-picture of a place and time. Would you use the term ‘free jazz’ for its first phase before it moves into more of an obviously composed piece?”

“Yes. The first part is completely improvised and if we perform it tonight it will be different yet again!”

“Now, at the age of seventy-four, you’ve accomplished so much – achieved so many accolades… Are there plans or dreams you’d still like to realise?”

“It might be nice to record some lovely arrangements that have been done for me over the years – particularly for orchestra. Of course it’s hard to do an orchestral thing and to pay for it! Though, in fact, there is a seed of an idea about me doing a concert for my birthday next year with the orchestra from the Royal Academy of Music. One potential problem is that the BBC commissioned some of the arrangements and we’re not sure whether they still have them. I don’t know if they shred things and who knows if they’re still there in their library…”

“Your next project?…Are you writing? And can you give us a taste of something we might look forward to?”

“Well I’ve just been over to see the guys in the trio [Klaus Geing and Glauco Venier] and we are thinking about the next recording project – music from films – so we’ve been hunting for things – some songs and bits of music that I’ll perhaps write words to.”

“Is there anything you would like to impart to singers who read this interview? What jazz singing wisdom would you like to convey?”

“Jazz singing wisdom? It’s enough to be able to communicate a song. Improvising with the voice is very difficult. I don’t think you have to do it to be a jazz singer so to not worry too much about trying to ‘be an instrument’. There are some people who are really good at it and some who aren’t but if you want to do it then have a go.”

Following our interview Norma went straight into a sound check with Nikki and the band, later giving us the remarkable performance we’ve come to expect and appreciate.

Lou Beckerman